Art of neon: light flickers on old British craft, but new show aims to keep it alive

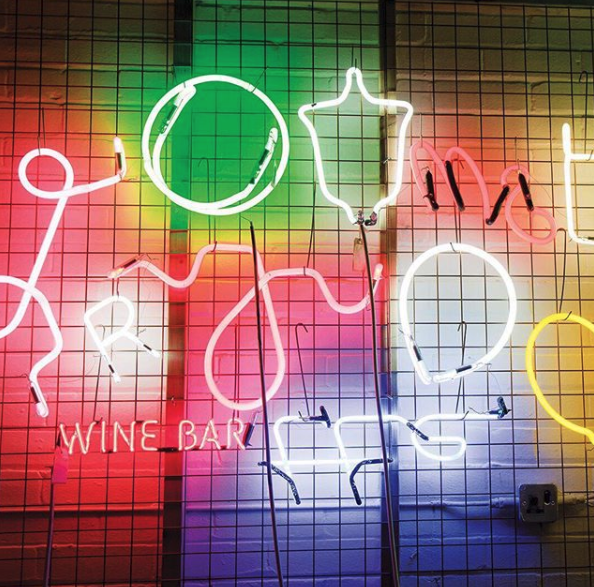

Across two galleries in Wakefield sit more than half a dozen tubes of light at least two metres tall, revolving on the spot and creating ethereal shapes in the air. These sculptures, created by the pioneering American neon artist Fred Tschida, make up a dramatic new exhibition in the city called Circlesphere, which will open later this month.

The artwork is a rare example of what is now a dying craft, with only a handful of neon makers left in the UK. Along with trades like ladder making, slating and straw working, neon making is considered endangered and likely to die out altogether if urgent steps are not taken to preserve it, according to the Heritage Crafts Association (HCA). Daniel Carpenter, HCA operations director, said neon-making skills are a “small but significant part of British culture” that, if lost, would be “nearly impossible” to bring back.

“Recording them for posterity isn’t enough, as they need to maintain a continuing lineage of transmission in order to survive,” he said.

“As well as having cultural importance in their own right – if they are valued and invested in – craft skills can become drivers for local economy, tourism, placemaking and community integration.”

Though the industry is in decline due, in part, to cheaper plastic and LED alternatives made in east Asia, Wakefield is one of the few places where neon is thriving, thanks to Neon Workshops, a specialist studio established 10 years ago by the artist Richard Wheater. A former student of Tschida, he organised the exhibition to showcase a different side to the bright, gas-filled tubes which Wheater said we tend to associate with “strip joints, sex shops and cheap takeaways”.

Wheater said: “[The audience] are going to see neon in a way that they haven’t before. And this is what art does when it works best, it gets them to look at something differently. That’s why it’s so great to have this platform, just to show people what it can be, how subtle it can be, how meditative it can be.”

Tschida, an artist and now retired professor of glass, was a key figure in turning neon from a craft that mostly provided signs for advertising to an art form in its own right.

Although he has been making neon art since the 1970s, the Wakefield exhibition is significant because it is the first time that Tschida has shown his work in Europe.

Wheater said: “Its aim is to put the record straight. I think it does him an injustice to say he’s a neon artist, I think he’s just an artist, a sculptor, and his interest is with light and movement.”

Traditionally, every neon sign was hand bent by a skilled glassblower working specifically as a neon signmaker. These tubes are then filled with a noble gas and electrodes are added at each end to give the gas an ionising charge, which produces the glow.

Though popularised in places like Paris and Las Vegas, the first neon gas-filled tube was created in London by British scientists William Ramsay and Morris Travers in 1898. Over the first half of the 20th century, West Yorkshire became the neon-making capital of Europe and remained so until the start of the 21st century.

Now Neon Workshops is picking up the mantle, having produced neon art that appears across cities all over the UK, at one point including a piece installed at London’s Southbank Centre, and internationally in countries such as Switzerland and Germany.

Wheater and his team are benefiting from a mild resurgence in true neon, which, though expensive, is long-lasting – remarkably, the first neon sign ever made in the 1920s still lights up – and one of the greenest forms of lighting available, as it uses low amounts of energy and is virtually fully recyclable.

Given that there has been no formal or established route into neon making since the 1990s, Wheater is keen to pass on his knowledge of the craft. He has an apprentice at Neon Workshops and he also runs courses in Wakefield and London for anyone who is interested in learning the traditional skill.

“There is just such a wide demographic of people on the courses,” Wheater said. “You have everyone from priests to long-distance lorry drivers. It’s great. Quite often they come out with some really, really cool ideas.”

… we have a small favour to ask. Tens of millions have placed their trust in the Guardian’s high-impact journalism since we started publishing 200 years ago, turning to us in moments of crisis, uncertainty, solidarity and hope. More than 1.5 million readers, from 180 countries, have recently taken the step to support us financially – keeping us open to all, and fiercely independent.

With no shareholders or billionaire owner, we can set our own agenda and provide trustworthy journalism that’s free from commercial and political influence, offering a counterweight to the spread of misinformation. When it’s never mattered more, we can investigate and challenge without fear or favour.

Unlike many others, Guardian journalism is available for everyone to read, regardless of what they can afford to pay. We do this because we believe in information equality. Greater numbers of people can keep track of global events, understand their impact on people and communities, and become inspired to take meaningful action.

We aim to offer readers a comprehensive, international perspective on critical events shaping our world – from the Black Lives Matter movement, to the new American administration, Brexit, and the world’s slow emergence from a global pandemic. We are committed to upholding our reputation for urgent, powerful reporting on the climate emergency, and made the decision to reject advertising from fossil fuel companies, divest from the oil and gas industries, and set a course to achieve net zero emissions by 2030.

If there were ever a time to join us, it is now. Every contribution, however big or small, powers our journalism and sustains our future.

Source: theguardian.com

Responses